Silicon Valley is still politely shrugging after the mildly interesting, but definitely important news broke yesterday that Alphabet’s founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin, also the founders of Google, were “stepping aside” from their leadership positions.

In a company blog post, the duo said it was time to simplify the two company’s command structures and that both of them would be replaced by Google’s current CEO Sundar Pichai, who has now assumed control of both companies. Well, at least on paper anyway.

This story is both exciting – Alphabet is probably the most important company in the world – and boring. Did anyone not see this coming?

As the Verge’s Dieter Bohn put it today:

In a strictly technical, definitional sense, this is an “era-changing” moment because there’s a new CEO for Alphabet. Larry Page and Sergey Brin, the founders of the company, are stepping back from running things and any time the founders change jobs, it means something. Arriving randomly on a Tuesday afternoon, it felt surprising and big.

But it also felt a little like a non-event, just a formalization of how things have been working anyway.

The consensus among technology journalists appears to be that Sundar Pichai is the sober, corporate-friendly leader that’ll keep the Alphabet umbrella competitive in a market that cares more about your next product than your last one.

Bohn says Pichai’s job was “to take Google’s products out of permanent beta. At the same time, he’s had to ensure future technologies — especially those based on AI — turned into real products. From a purely product perspective, which of course includes the lucrative ad products that make the whole thing go, Pichai has been very successful.”

It’s hard to argue against Pichai’s success. Few companies have the commercial power that Google does. But, what does commercial power have to do with Google? Was I really that naive when I bought everything Brin and Page were selling in the beginning?

After 9/11 I needed to believe that the future would be better than the present. What Page and Brin did during the subsequent decade made us all believe that technology had advanced to the point where the smartest people in the room can snap their fingers and change the world for the better.

Yet, the company’s actions over the next decade showed us that our new relationship energy had blinded us to the truth about Google: it’s a magic trick, an illusion. Don’t get me wrong, Google saves lives and is responsible for more technological innovation than most of its peers.

However it is a mathematical certainty that someone who randomly throws a trillion darts at a dart board will score more bullseyes than someone who takes a few well-aimed shots. Google can afford a lot of darts so it’s never had to worry much about aim.

It doesn’t seem like Brin and Page ever focused on what could go wrong. Changing the world is much easier when you put all of your energy into wondering what could go right. Unfortunately, things haven’t always gone to plan:

- Fired Google employees will charge the company with ‘unfair labor practices’

- Google fined a record $5B for breaking EU antitrust laws

- Thousands of Google employees walk out to protest harassment, inequality

- Amazon gets patriotic while Google embraces censorship

- China’s censored Google is an ethical catastrophe

- Google employees quit over the company’s military AI project

- Congress is fed up with Google after it hid major bug for months

- Google Walkout organizers publicly accuse Google of punishing them

- Google employees protest suspension of two activist colleagues

- Google Cloud’s new AI head comes with his own ties to the Pentagon’s Project Maven

- German protesters clash with police over proposed Google campus

- Alphabet is investigating Google’s handling of recent sexual harassment claims

- Google exploited homeless black people to develop the Pixel 4’s facial recognition AI

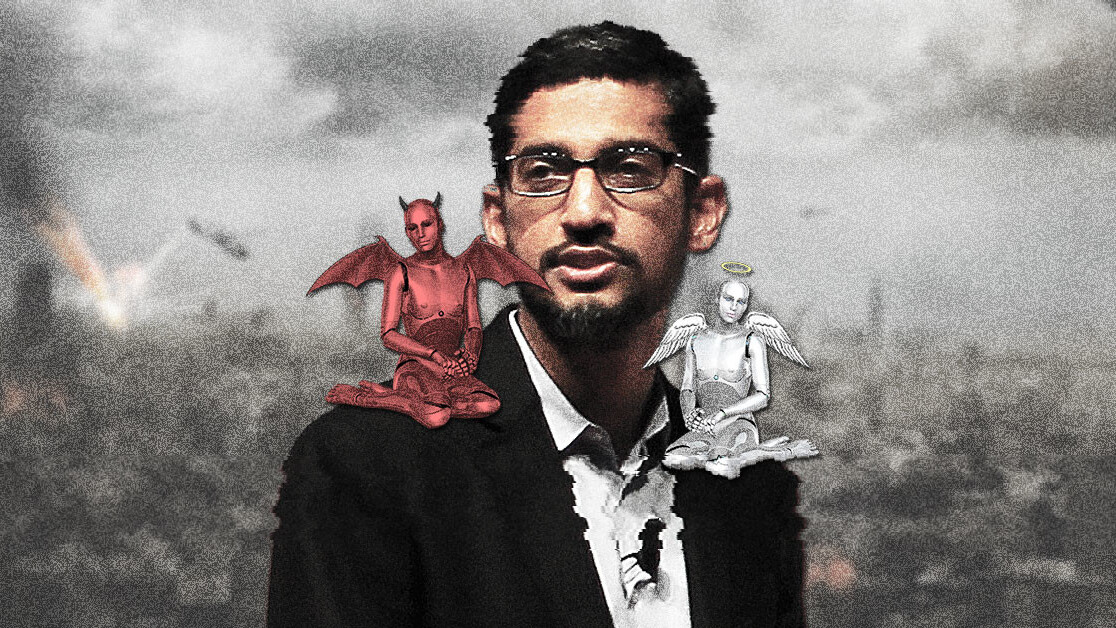

And this is just a smattering of the recent stuff under Pichai’s leadership. This isn’t meant to point out that Pichai is the wrong person for the job. He’s perfect for Brin and Page. Pichai’s the person who massages their reality.

When the media lashes out we’re blaming Pichai, not them. And even then our outrage only lasts until the next technology conference. For years this paradigm has worked very well for Alphabet and Google.

But after decades of turning a deaf ear and a blind eye to the potentially catastrophic ramifications of paradigm-shifting technologies, it seems like the company’s leadership can no longer feasibly feign ignorance. The world watched last year as it changed its motto from “Don’t be evil” to “Do the right thing.” The former statement, it feels, applies to the humanity of the company’s employees. But “do the right thing” seems like something you tell someone before adding “for the company.”

Google’s changed. It’s just as idealistic as ever, but as Dr. Fei-Fei Li found out, it’s an incubator for ideas that places infinitely more value on the ideas themselves than the ramifications of those ideas. It’s a company that’s always stuck on the first draft of a product because it never takes the time to fully develop anything to truly serve humanity first. Sundar Pichai and the Googlers who work for him aren’t beholden to the greater good or their customers, despite what they may actually believe. Google isn’t beholden to money either, it has plenty; it merely wants more.

No, they’re perpetually fixated on a broken ideal. Under Pichai, Googlers are members of the cult of personality that centers around Brin and Page’s dogmatic view that technology for technology’s sake – moving fast and breaking things – is the key to innovation.

As long as Google steams forward with no regard for what happens in its wake, the allure of the church of Brin and Page remains stronger than any researcher’s objections or politician’s call for regulation. Google makes progress look easy by avoiding some hard truths. But even geniuses like Brin and Page can’t always stride gallantly forth into the future when pesky experts keep pointing out that Google’s trailblazing a dangerous path.

In this respect, Sundar Pichai is the antidote to Google’s founders’ lingering consciences. His cool, measured presence reinvigorates that initial spirit of optimistic capitalism that makes it easy to dismiss questions like “what negative effects could gendering virtual assistants or releasing inherently-biased AI products to the public have on our society?” as “small picture” problems. He inspires those around him to live by platitudes instead – Google’s making the world a better place, look at all the good it’s done.

Pichai is the leader that can tell you with a straight face that his dirty hands are clean and believe it. While Brin seemingly gets wishy-washy over tough topics like censorship the moment someone makes a suggestion that eases his worldview into a more company-friendly slot, Pichai can quietly and calmly embrace and defend such repugnant concepts as though we’re the unethical ones for not understanding his big picture. That’s quite a talent — one he shares with his predecessor.

And when it comes to Page, who always seems to have the answers, he can no longer lead Alphabet and Google from his lofty vantage point as the smartest daydreamer in the room without also facing the company’s perceived descent into the same sludge that DuPont, Exxon, Facebook, and Uber occupy. He could grow up and pivot as Bill Gates seemingly did, but he won’t. He’s got Sundar Pichai to protect him from that.

Brin and Page are moving out of Pichai’s way so that he can do what he does best: whatever the hell they tell him to.

The startup that made us all believe in innovation again just became a conservative enterprise. Let’s check back in a decade to see how that works out.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.