Environmental crime is a strange beast.

It’s extremely broad – it spans everything from illegal wildlife trading to unregulated fishing to dumping hazardous waste.

It’s very lucrative – Europol estimates the annual value of transnational environmental crime to be in the hundreds of billions of dollars.

It’s mostly invisible – catching culprits in the act is challenging for authorities.

And on top of all that, enforcement of sanctions is difficult when accurate quantification of damage is nearly impossible – many types of environmental disasters play out over a span of months or even years.

It’s a problem so big, that the police force of one of the world’s smallest countries is planning on reaching out to citizens to help them manage it.

31 million liters of hazardous waste

“It all started after the airing of the documentary Beerput Nederland. It mostly dealt with a Dutch company buying up 31 million liters of hazardous wastewater in Angola, and allegedly illegally disposing of it in the waters around Amsterdam,” Sander Huisman told me.

Huisman is manager of Shared Intelligence, a project the Dutch police force set up to involve more stakeholders in the fight against environmental crime.

The documentary brought to light the way Dutch authorities were completely failing to deal with crimes of this scale – even going as far as involving the offending company in the creation of new environmental legislation.

As one of the interviewees, emeritus professor of the technical university of Delft Ben Ale said, “[It seems like] the government is not here to protect citizens against polluting companies, but to maximize the profit of those companies.”

The documentary by Dutch filmmaker Wilfried Koomen brought to light how the Dutch government often turned a blind eye to polluting companies. Repeat offenders are let off with warnings instead of sanctions, and crimes like mixing fuel for ships with toxic substances are tolerated to coax more traffic into Rotterdam’s port.

Citizens should help out

Beerput Nederland led to a parliamentary inquiry into the matter, but it also led to personal indignation that prompted Huisman and a group of colleagues to start thinking of solutions.

“We started brainstorming about how we could hold on to and use that feeling to fight these types of crimes, and also how we could work with citizens to tackle environmental crime, said Amir Niknam who co-created the Shared Intelligence project.

“The problem is that environmental crime is invisible a lot of the time. Perpetrators are committing an invisible crime that leads to invisible damage,” he adds.

At the moment, the police and other environmental authorities function reactively. “After we get a report, the crime has already happened, and all we can do is clean up the waste,” Huisman says. “So we need to find and identify this pollution earlier in the process.”

Using sensors and open data, the Shared Intelligence team wants to be able to act sooner and make the crime more visible. Not only for authorities but for citizens as well.

“We want to make the environmental quality of their surroundings visible to citizens, in their town or neighborhood,” he said. “And we want to give them the possibility to add information of things they’ve noticed or seen themselves.”

Cleaning up the mess

The first step in the plan is to develop a network of connected sensors that can pick up different types of environmental crime instantly, transmit that to a central point, and thus help authorities to catch perpetrators in the act.

“At the moment all we can do comes after the act, we’re just cleaning up the mess. We need to identify these crimes earlier in the process. We want to be proactive, and we need everybody’s help in doing so.”

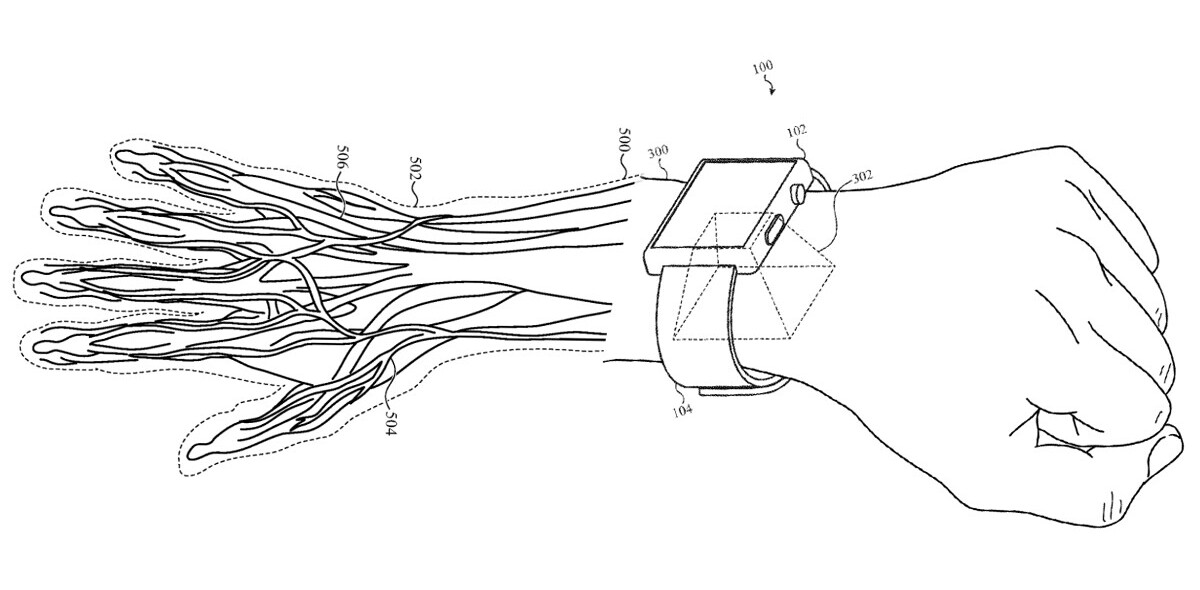

The second step in the plan is to connect more data sources, allowing citizens to more effectively report different types of crimes. Currently, the police is looking into the development of cheap sensors citizens can literally place in their backyards.

The sensors – which could range from robotic ‘eels’ that swim around sniffing for pollution to small chemical sensors – would constantly collect info about their surroundings, and pass the data on to a central point.

All these collected data would be collated in the dashboard and be publicly accessible to both citizens and the police. “The idea is that real-time information about things like the dumping of waste in water or pollution of soil leads to notifying police dispatchers.”

“This should improve authorities’ abilities to catch criminals in the act,” Huisman hopes.

Defining pollution

A big challenge they’re still facing in developing those sensors is one that’s probably well known to environmental police all over: What counts as pollution? What concentration of drug substrates in water is acceptable, and what points to a nearby XTC lab? “We’re still working on these problems,” Huisman told me.

Nonetheless, giving citizens access to sensors and data about their immediate surroundings seems like a good way to go. Professor Jan Hendriks, Head of Environmental Science at the Radboud University in Nijmegen agrees. “Just like how people now are aware of noise and smells, we could become aware of pollution that we can’t register with our own senses. This could lead to changes in awareness and behavior.”

Huisman does acknowledge that tackling environmental crime is a huge problem that will probably take multiple years. “The problem is extremely diverse, it ranges from incorrect disposal of electronic equipment to instances like in the documentary.”

His team has taken a startup-like approach; by developing, applying, and testing small steps at a time they’re hoping to iterate quickly on solutions. That’s necessary because the project involves many different types of authorities. “We’ve got people from the water authorities, environmental services, a crime economist, environmental detectives, engineers, and more.”

In addition, they’re reaching out to parties inside and outside of government to help determine the best way to solve this messy problem. So far, they’ve gotten interested responses from universities and the National Institute for Public Health. They’re also calling for startups working on IoT devices to pitch solutions.

“None of us are working on this because we have to, we’re all working on it out of a sense of that we simply have to do something about this,” Huisman said.

Which is the same feeling they’re hoping to create among the citizens by showing them what’s going on around them. Because even though environmental crime might be hard to grasp, if it’s going on in your backyard, you’re sure to act.

Got an IoT solution that can help fight environmental crime? Sign up for the Vodafone TNW IoT Challenge before August 10.

Get the TNW newsletter

Get the most important tech news in your inbox each week.